Monitoring employees in the name of productivity or security can cause a lot more problems than it solves.

On Halloween 2022, National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo released a memo that likely horrified plenty of executives. She announced her intention to “protect employees … from intrusive or abusive electronic monitoring and automated management practices.”

In other words, the NLRB declared war on bossware. And it’s not alone. Beyond Abruzzo’s memo lies an evolving, growing array of laws and regulations that seek to protect employees' privacy rights against employee monitoring software, otherwise known as bossware.

Numerous countries and a handful of US states, such as California and New York, have already imposed restrictions on how companies can digitally surveil their employees. And given the public sentiment swaying against bossware and toward privacy, we can likely expect more laws and tougher enforcement from regulators.

If you’re in charge of purchasing, implementing, or maintaining employee surveillance tools at your organization, this is a good time to step back and evaluate what tools you’re using and how you’re using them.

What is bossware?

“Bossware,” a term the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) coined in 2020, refers to technologies that companies use to monitor employees on their devices. What this looks like varies depending on the workplace.

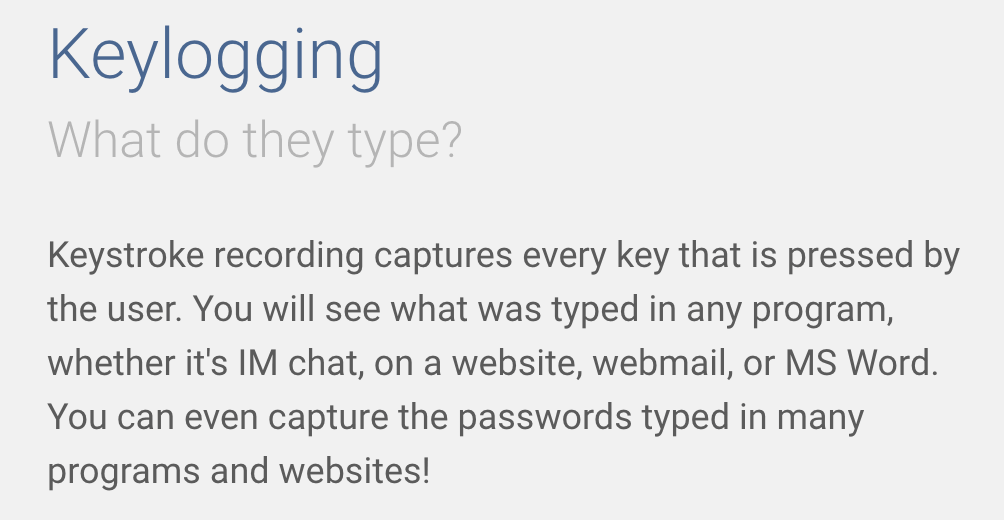

Abruzzo’s memo cites things like wearable devices for warehouse workers and GPS cameras on truck drivers, but she pays particular attention to computer-based surveillance, calling out “keyloggers and software that takes screenshots, webcam photos, or audio recordings throughout the day.” The memo goes on to mention tools that keep watching when employees are off the clock, such as those that “track employees' whereabouts and communications using employer-issued phones or wearable devices, or apps installed on workers' own devices.”

Beyond such obvious types of surveillance, bossware can come in more subtle forms, like tools that aggregate employee sentiment from emails or their private social media – ostensibly to gauge their job satisfaction.

Bosses who use this technology report that their primary concern is productivity. According to a Digital.com survey, the top use cases are checking how employees spend their time (79%) and confirming whether employees are working the entire day (65%).

These reasons also overlap with security concerns. The same study shows that 50% of bosses use employee monitoring tools to check whether employees are using work devices for personal use, which touches on both security and productivity. And there are plenty of tools that aren’t designed primarily for surveillance but are still prone to misuse–for instance, data loss prevention (DLP) tools that capture everything a user does.

Why now? Remote work and the bossware backlash

The idea of remotely monitoring employees has been around for decades, and many employee monitoring software vendors have been in business for years. But three changes have made the backlash to bossware swifter and harsher than many would have expected:

The development and proliferation of more advanced, automated forms of surveillance.

The shift toward remote work.

The rise of privacy rights and the labor movement.

Let’s look at each of them a little more closely.

Automation enables spying at scale

In the past, keeping tabs on employees required a human touch. Scientific management, sometimes called Taylorism, emerged in the early 1900s and encouraged factory supervisors to time their employees with stopwatches. Later, CCTV footage helped bosses mind the store, but even that type of surveillance was constrained by the ability of people to go over the footage.

Today, bosses don’t have to skulk around break rooms to spy on workers; they can require employees to install software that logs their keystrokes, accesses their webcam, and more. Bosses can deploy these tools at scale and run them passively. That means bosses can monitor all employees as standard procedure, not as a result of individual cases of suspicious activity.

Companies can now read emails and analyze the sentiment of their contents, track employees on social media, monitor the movements and clicks of employees' mouses and keyboards, identify which applications employees are using and for how long, and record webcam video. Some bossware can even aggregate all of this data so bosses can identify unhappy workers and prevent employees from taking collective action.

These tools mark a qualitative leap over earlier forms of surveillance, and their widespread use on employees – who may not even be aware they’re being watched – makes plenty of people uncomfortable.

Remote work made bossware more intrusive

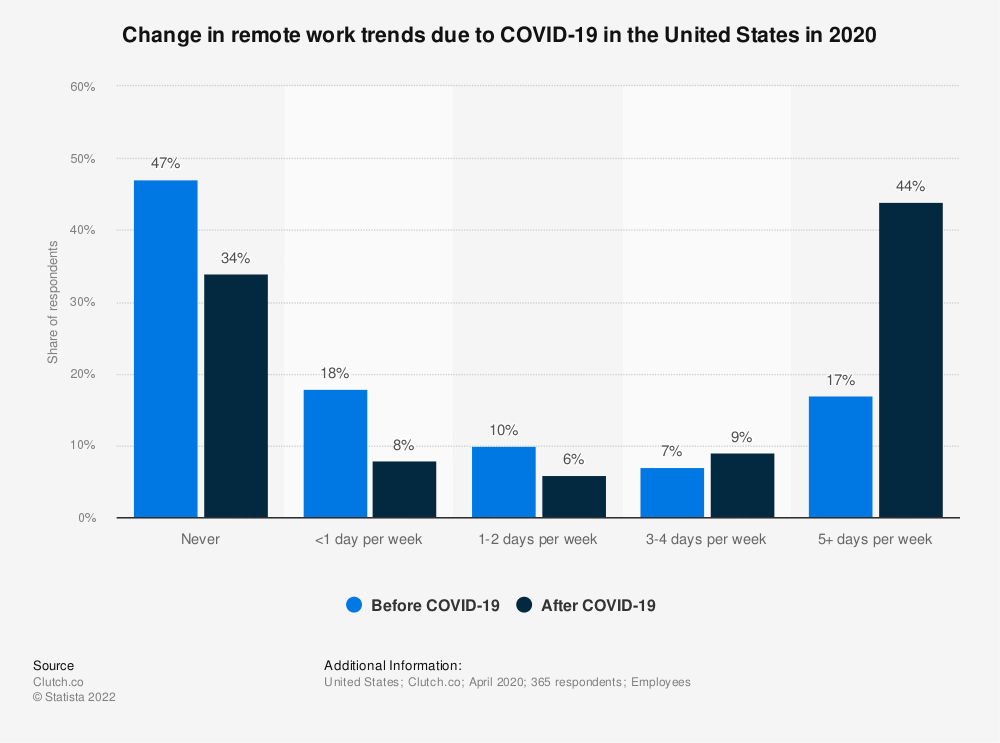

The current rebellion against bossware and workplace surveillance began with the COVID-19 pandemic, which accelerated the remote work trend.

The rise of remote work makes employee surveillance even more intrusive because employees are likely to be working from home or using personal devices, and bossware tools often aren’t capable of recognizing those boundaries. The EFF found, for example, that many bossware products “don’t distinguish between work-related activity and personal account credentials, bank data, or medical information.”

This failure to distinguish between professional and private life is especially stark when we consider webcams. In an office setting, requiring employees to keep their webcams on during the workday might be irritating. But the same policy is much more invasive when employees work from home, and the webcam captures their non-consenting partners, roommates, or children. And it’s even more troubling if the webcam is on without the worker’s knowledge.

The labor movement and the “techlash”

The fight against bossware isn’t happening in isolation; it’s piggybacking on the victories in the larger movement for consumer privacy and organized labor.

When Facebook first became popular, for example, many users didn’t care – or didn’t realize they should care – where their data went. Now, after years of data misuse and breaches, many people are wary of giving companies access to their personal data. Laws like the EU’s GDPR and California’s CCPA have sprung up to prevent unnecessary data collection.

Workers might not be able to join in the privacy backlash were it not for the resurgent labor movement and a tight market that has put employers at a disadvantage for the first time in decades. Gallup Research from 2024 shows union approval is at its highest level since the 1960’s. Though unionization in technology companies is still relatively rare, Protocol research shows 50% of tech workers are interested in joining a union.

And as interest turns into action, workers will have a greater ability to protest intrusive surveillance, especially when it’s illegally used to prevent them from organizing.

Bossware and the law

The unspoken truth, known by many executives, is that laws are only as powerful as their enforcement mechanisms. The NLRB, referenced at the top of this article, is chronically underfunded and understaffed. After decades of the Reagan-inspired “starve the beast” mentality, government agencies are often weaker than the industries they are tasked with regulating.

But in the U.S., the Biden administration has provided over something of a renaissance in labor, buoyed by Presidential approval. And around the world, regulators are holding scofflaw companies to account.

Labor laws are on the cutting edge against bossware

The NLRB is taking a stand against bossware because of how frequently it is used to suppress or discourage workplace organizing. For example, a “productivity tool” that tells bosses who each employee speaks to and for how long has a clear potential for misuse.

Abruzzo writes in her memo that numerous types of bossware already run afoul of, in her words, “settled Board law.” For example, monitoring “protected concerted activity” (i.e. workplace organizing) has been illegal for decades.

This kind of monitoring was more clear-cut when it involved taking pictures of picket signs and video recording employees in break rooms, but now, the NLRB is looking into passive, virtual monitoring. And for good reason: in an interview with OneZero, the “employee listening” platform Perceptyx explains that it offers, by default, a “union vulnerability index.” With it, the company explains, employers can log into their platform and see that “20% of that group is at risk of unionization.”

Abruzzo also makes clear that if companies use tools that aren’t strictly for employee monitoring to police protected activities, they run afoul of Section 8(a)(1). In another article, we covered Slack’s privacy policy and explained how bosses could see all of your private messages. A company could face the consequences of using Slack like bossware (such as if a manager downloaded an employee’s private messages to see whether they were comparing their salaries or considering collective bargaining).

Beyond extant law, Abruzzo also writes about using “settled labor-law principles in new ways.” This is not an uncommon legal practice because the law, notoriously slow and difficult to update, often evolves via analogy. The Interstate Commerce Act, for example, was established in 1887 to oversee the railroad industry but was an important legal framework for regulating the petroleum, trucking, civil aviation, and telecommunications industries for many decades after its establishment. Regulatory bodies compared new industries to railroads and applied previously settled regulations to new contexts.

The same pattern could play out for bossware. In 1992, the NLRB came down on Sands Hotel & Casino because management assigned guards to monitor employees using binoculars. At first glance, such a ruling might not seem to apply to you. But the courts could very well decide that keyloggers are effectively modern day binoculars – meaning a lot of bossware could suddenly become illegal without the creation of new laws.

Federal and state regulations

The NLRB isn’t alone in taking on bossware, though it might be leading the charge. Abruzzo notes that she wants to take an “interagency approach” to bossware and work with agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Labor to limit the use and abuse of employee monitoring.

And that’s not all: The Center for Democracy and Technology points out that bossware could also be illegal by way of numerous other laws, such as:

The Occupational Safety and Health Act could punish companies for limiting bathroom breaks via monitoring and productivity quotas.

The Americans with Disabilities Act could punish companies for treating disabled employees differently due to the results of employee monitoring.

Federal wage and hour laws could punish companies for automatically docking employee wages when they leave their workstations.

The Family and Medical Leave Act could punish companies for restricting employees with qualifying medical conditions from taking intermittent breaks.

So far, we’ve just covered federal laws, but state laws are catching up as well. The laws differ from state to state: New York, Connecticut, and Delaware laws all require employers to notify employees of monitoring activities upon hiring them. And as of January 1, 2023, California updated its major data privacy law, extending some of the protections offered by the CCPA, via the CPRA, to employees.

International bossware laws

Outside the U.S., many countries are much more aggressive in balancing the rights of employees against employers. And for companies with remote workforces, this can come as a rude awakening.

A particularly good example occurred in 2022 when a Dutch court fined a Florida firm for punishing an employee who refused to keep his webcam on all day on the grounds that it made him uncomfortable.

In response, the firm fired him, citing insubordination. The court disagreed, ruling that video surveillance of an employee constituted a “considerable intrusion into the employee’s private life.” The takeaway here isn’t that companies should stay out of The Netherlands, of course – it’s that a remote, globalized workforce will come with diverse laws and cultures around employee privacy.

As a small sample, consider a few other European laws:

In Austria, the Austrian Labor Constitution Act requires employers to either get the consent of all employees or of an employee work council before monitoring them.

In France, the French Data Protection Authority ruled that, outside of a “strong business justification,” companies cannot use keyloggers.

In Germany, employers can’t use much of the passive monitoring we’ve talked about so far. Instead, German employers can only implement monitoring after establishing reasonable suspicion of unprofessional behavior.

Four questions to ask before implementing bossware

So far, we’ve sketched the broad strokes of the legal risks of bossware, but how do you assess it on an individual level if you’re a CISO, an IT administrator, or a manager?

Here’s a good place to start to assess whether a particular form of surveillance is legal or necessary.

1. Does it suppress unionization?

We’ve already talked about the potential for bossware to be a de facto union-busting tool, which is clearly illegal. So if your company is investing in a tool for purely productivity or security-related purposes, then discuss how you can prevent it from being misused to suppress organizing.

It’s also worth considering how an existing union might react to surveillance. In her memo, Abruzzo not only explained how the NLRB would enforce extant laws but signaled that the NLRB would likely support unions complaining about bossware. The previously cited Digital.com research shows that 88% of employers terminated workers after implementing bossware, so new unions would undoubtedly examine these kinds of tools. A 2014 NLRB ruling shows that even giving the impression of unlawful surveillance can make companies liable.

2. Does it pose a major risk in the event of a data breach?

A major reason companies might want to limit the collection of personal information (via bossware or otherwise) is that a data breach could expose personal information to bad actors.

Companies might get punished, then, not for the usage of bossware but for poor security practices that made personal information captured by bossware vulnerable to attackers. It’s a good reason to return to the classic data security principle of data minimization and consider whether the benefits of bossware outweigh the risks of storing such sensitive data.

3. Does it open you up to personal liability?

Companies establish LLCs, as the name implies, to limit liability. Companies can collapse while individuals can move on. Increasingly, however, government agencies are targeting individuals.

Joe Sullivan, former chief security officer for Uber, for example, pled guilty in 2022 to covering up a data breach. Employers will want to be especially careful about implementing dubiously legal policies if they, as individuals, can be found liable.

4. Does it violate discrimination laws?

As we wrote above, Abruzzo emphasized taking an “interagency” approach to enforcing laws against workplace surveillance. That means companies have to watch out for restrictions coming from multiple directions. One very likely direction is via anti-discrimination laws.

For example, a company might discriminate against a mother by punishing her for taking breaks to breastfeed, among a host of other possibilities.

Surveil with care

Legal threats aside, there’s a simpler reason you should push back against bossware at your organization: It’s bad for workers, and there’s compelling evidence it’s bad for employers, too.

For employees, bossware can create intense feelings of stress and anxiety. ExpressVPN research shows that 56% of monitored employees feel stress and anxiety about surveillance, and 32% take fewer breaks because of it. Are short-term productivity gains worth long-term employee unhappiness and burnout?

For employers, even if we assume that bossware increases productivity (and researchers are divided on whether it does), its overall effectiveness is doubtful. Employee paranoia and resentment come at their own costs. A Harvard Business Review study showed, for example, that monitored employees were “substantially more likely to take unapproved breaks, disregard instructions, damage workplace property, steal office equipment, and purposefully work at a slow pace, among other rule-breaking behaviors.”

As we covered at the beginning, beneath the desire to monitor employees is the desire to ensure productivity and security – both of which are reasonable goals to pursue. Bossware, however, is a blunt instrument, and likely the wrong instrument, for succeeding here.

If you want to monitor productivity, focus less on behavior and more on results. In other words: if an employee is getting their work done, it’s really none of your business how often they go to the bathroom.

If security is your concern, privacy should be as well – even if that seems counterintuitive at first. The more you intrude on employees, the more likely they are to try to evade surveillance altogether, which increases the likelihood of unsafe behaviors on unmanaged devices. Instead of tracking their every move, be surgical and thoughtful about the data you collect.

And if you really, really need to monitor employees: be transparent. Your employees deserve to know how you’re monitoring them and what information you’re collecting and storing. Plus, if you try to be secretive and your employees find out, the blowback could do irreparable damage to your company’s culture. You’re much better served by bringing your policies out into the light.

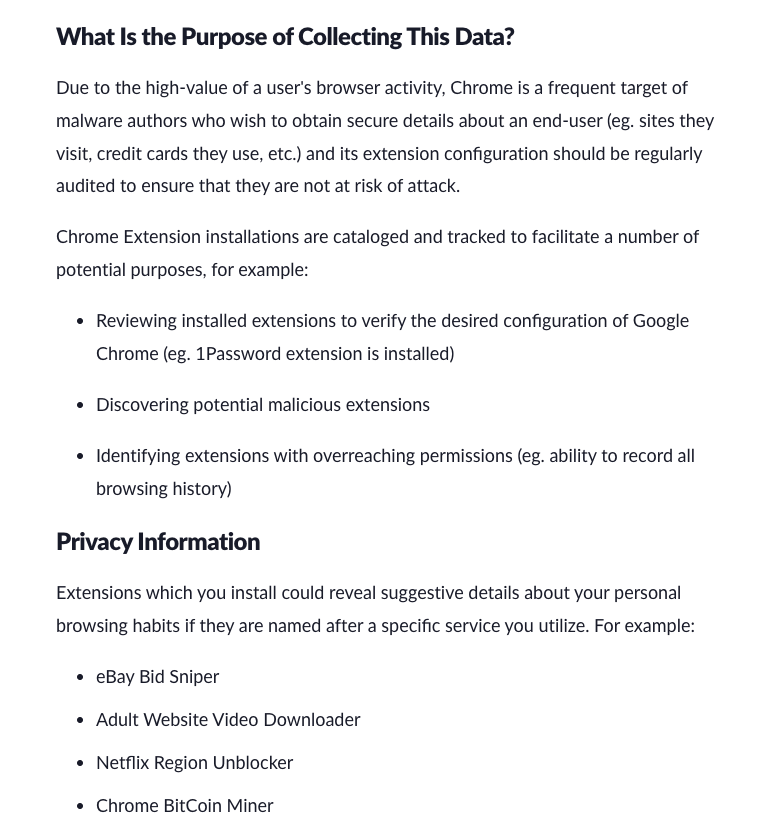

Here at 1Password, for example, our Device Trust solution collects data about employee devices, but it does so in accordance with our philosophy of Honest Security. We practice minimization; we collect only the data we need to keep our customers safe. For example, we keep track of an employee’s browser extensions – because those can present a security risk – but we deliberately don’t monitor browser history. Likewise, we practice transparency; every end user can visit our Privacy Center to see what data we collect and what it can reveal about them.

This approach is the best way to get your workforce on your side, while you stay on the right side of the law.

Want more security and IT stories like this one right in your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter!

by Nick Moore on

by Nick Moore on