I’d like to take a moment to talk a little bit about how people who study password behavior go about their job. In the process, I would like to thank all password researchers and, in particular, Mark Burnett for both his years of excellent research and the help he has provided to other researchers. He is unequivocally one of the good guys, even if portions of the technical and popular press have entirely misunderstood the impact of his support for the research community.

Before getting into any detail, I would like to make it clear that Mark’s posting of 10 million passwords on Monday did not reveal any new information to hackers, and did not enable any new attacks. All of the information he packaged was already public, and Mark’s preparation made it even less useful to bad guys. For details, it’s best to read his own FAQ.

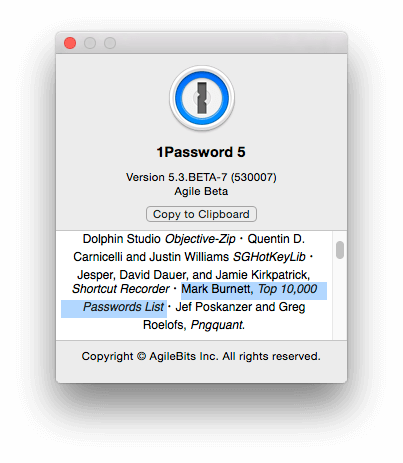

Of course, you, our readers, will all be using 1Password to help ensure you have unique passwords for each and every site and service.

Researching secrets

One of the biggest difficulties in studying password behavior is that people are supposed to keep their passwords secret. Because of this not-so-minor drawback, there are two ways to get real data on people’s behavior.

One way is to conduct experiments and simulations. There is some really exciting research along these lines, particularly from Lorrie Cranor’s group researching Usable Privacy and Security at Carnegie-Mellon University. But there are many others contributing to that research.

One of the advantages of these experiments, which almost no other method offers, is that they help us figure out how well people can use and remember passwords. Of course, 1Password saves you from having to remember all but one (or a very few) of your passwords, but those passwords need to be strong. We rely on the research conducted by the academic community on password learnability, usability, and memorability when offering our own advice on creating better Master Passwords.

The second way to analyze people’s behavior with respect to passwords is to study the data that comes from password breaches. For example, when RockYou was hacked in 2009, the attacker published a list of 32 million user account passwords. Much of the advice you see today about most common passwords comes from the study of the RockYou data. Note that not all breaches involve revealing passwords. The recent breach of Anthem, for example, didn’t reveal customer passwords.

Pretty much everyone who studies password behavior grabbed a copy those RockYou records. Professor Cranor, who I mentioned above, even made a dress based on the most popular passwords found on in the RockYou data. Although we do not condone such breaches, we all make use of the data if it is published.

It is almost certainly true that only a small portion of such breaches are made public. Many of the criminals would like to keep both the fact of the breach and any passwords they obtain secret so that they can be exploited before people change those passwords. Sadly, the criminals have more data than we do, so they know more about actual password practices than we do.

One of the many uses of this sort of data is to figure out what the most common passwords are. Lists like the ‘top 10’ or ‘top 100’ passwords are often published in attempts to shame people to make better choices. But Mark’s earlier publication of the top 10,000 passwords has made it into 1Password itself. In addition to other tools and guidelines, we use that list in the Mac and iOS versions when calculating password strength.

For big data sets, like RockYou or Adobe in November 2013, I will usually make a point of getting a copy. That way, I can do my own research on some of these datasets, as well as read about the analyses that others do.

Tracking password dumps

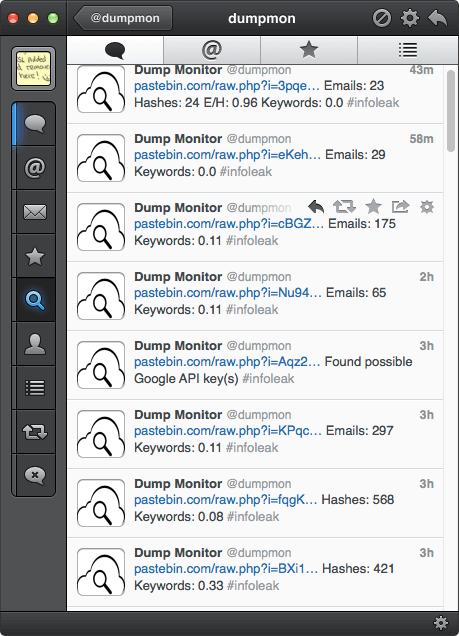

There are smaller data sets published very frequently, but sporadically, on sites like Pastebin. In fact, there is a handy Twitter bot, @dumpmon, that reports them.

To make things more confusing, many of the Pastebin posts make false claims about their data. They will claim that it is new data from, say, Gmail, while in fact it is old data drawn from previously published data. Quite simply, it is a substantial chore to watch for such data, evaluate it, and organize it into usable form. It takes skill, dedication, and analysis to do that.

I’m sure that I am not alone among those who study passwords to say that I am glad that Mark Burnett has been doing that work so that I don’t have to. Mark has been studying these for many years now. He has always shared his research results with the community, and has been very helpful when people (like me) ask him for some data.

When someone asks Mark for some of his data, he has to worry about removing credit card information that may be part of one leak, or revealing information about the site from which the username and password were obtained. Despite the fact that information has already been made public, he correctly does not feel comfortable re-releasing it. This is why he prepared the sanitized list that he released Monday.

What have I learned studying these 10 million passwords?

To be honest, I haven’t really dived into to studying these. I’m lazy efficient and patient, and am waiting for others to publish their results. However, if I don’t see certain types of analyses that I believe would be useful, I’ll roll up my sleeves and take the plunge.

But in playing with these for about 10 minutes, I (re-)learned a couple of things:

- Modern computers are fast enough that I can actually do much preliminary poking around using AWK.

- I was able to say “I told you so” to some friends about some clever passwords that were far more frequent than they’d imagined.

- I confirmed (as I did with the Adobe set), that David Malone and Kevin Maher were correct when they concluded that – despite appearances – passwords frequency does not follow Zipf’s Law.

- I hadn’t used Transmission/BitTorrent in ages, and no longer needed to seed the FreeBSD8.2 iso (The password list was made available via torrent).

- Update: Someone actually used “correcthorsebatterystaple” as a password, illustrating the dangers of presenting examples when explaining password creation schemes.

I do not wish to give the impression that I won’t be able to make valuable use of the data. There are a number of interesting analyses I would like to run. In particular, I would like to see if I can identify passwords created by a good password generator, but that will be a long and hard project. Broadly seeing what password creation schemes are the most popular would also be useful. I may use Dropbox’s zxcvbn password analysis engine to make a rough pass at that.

And there is no question that Mark’s collection, tidying, sanitizing, and releasing of this data will help us good guys learn more about password behavior.

by Jeffrey Goldberg on

by Jeffrey Goldberg on