The details are still vague, but it appears that the encrypted passwords of 35 million Steam users have been captured by bad guys. Note that there were two breaches. One was of Steam forums, the other is of their main user database. I am just discussing the later here as it involves many more users.

The passwords in the captured database were “hashed and salted”, which means that if you were using a strong password (say one generated by 1Password’s Strong Password Generator) you should be unaffected. Also if your password there was only used for Valve Corporation’s Steam game platform, then you don’t need to change it on other sites. Valve has not released details about exactly how the passwords are salted and hashed, so we should assume that weak passwords there are still vulnerable to crackers.

Tips for checking for duplicate and weak passwords

It’s really really important to have strong and unique passwords. So we’ve written about those before. You can read more about finding duplicates in 1Password for Mac and finding them using 1Password for Windows.

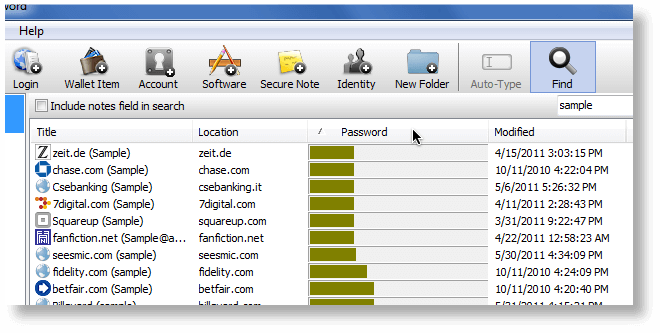

But for the very short version, on 1Password for Windows, you can sort your passwords by strength.

and in 1Password on the Mac you can search for specific passwords, which can help you find duplicates.

“Hashed and salted”

Websites should store your passwords in an encrypted format, typically using a “hash” function. The crucial characteristic of a hash algorithm is that it is unfeasible to calculate the original password (or other data) from the hash. For example, if we take the string “My voice is my passport, verify me” and run that through the (outdated) MD5 hashing algorithm, we get “7be5e25ce0fe807127c694c9bcb0008b”. If you have no prior reason to suspect what the password is, there, is no feasible way of computing this backwards.

Now suppose that someone has used the most common password out there, “123456”. The MD5 hash of that is “e10adc3949ba59abbe56e057f20f883e”. Couldn’t the bad guys just compute the hashes of some common passwords and then look for those hashes in the database? A quick scan of the database for “e10adc3949ba59abbe56e057f20f883e” should get you all of users who have “123456” as their password.

This is where salting comes in. Systems add a random something, called “salt”, to the password before hashing it. So if the random salt for a particular user is “4c8x” then what would get hashed would be “4c8x123456” and then what gets stored is both the salt and the hash of the salted password. Maybe something like “4c8x+70914eddcc1e5ad56f18076f7d2433cf”. The salt isn’t secret, but because it will be different for each user, the attacker can’t simply pre-compute the hashes for common passwords. It also means that if two users have the same passwords, the hashes will be different.

Salting passwords pretty much essential. Any site that isn’t salting passwords before hashing isn’t, well, worth their salt. Databases of this sort do get stolen, and the designers of these systems need to take that into account. It’s nice to know that Steam didn’t make the same mistakes as Sony.

For higher security passwords and for things that attackers have easier access to, salting isn’t enough. For those cases (like your 1Password Master Password) a cracker thwarting key derivation function is needed. I’ve written about our use PBKDF2 for those who would like to understand what we do to protect your master password.

by Jeffrey Goldberg on

by Jeffrey Goldberg on

Tweet about this post