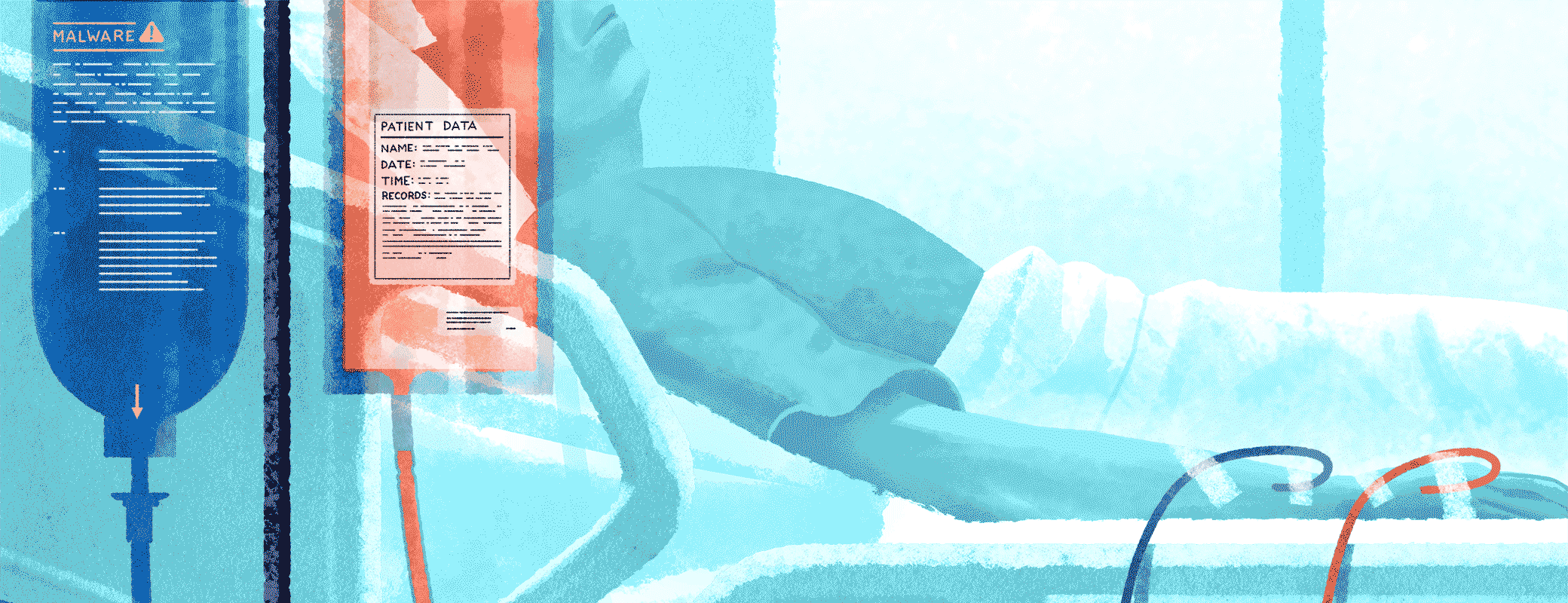

When the medical mission is at odds with security policies, patients and clinicians suffer.

Do you suffer from nosocomephobia, the intense fear of hospitals?

Maybe it’s because you’re afraid of blood, disease, or fluorescent lighting, but there’s another risk to consider – your data.

Hospitals and healthcare more generally are at some of the greatest risk for cyberattacks of any industry. A 2023 Ponemon Institute study found that 88% of healthcare organizations had at least one cyber attack over the past 12 months, and were specifically susceptible to ransomware and business email compromise (BEC) attacks.

It’s easy to see why. Threats actors know how sensitive healthcare data is: if they release patient medical records, the provider’s reputation is ruined. And if they shut down a hospital’s operations by locking down their systems, people die. 43% of respondents in the Ponemon study said a data loss or exfiltration event impacted patient care. Of those 43%, 46% said it increased the mortality rate.

Given the extremely high stakes, one would think that practicing good security would be a priority for any healthcare organization, but instead, clinicians regularly engage in practices that would send a security professional into cardiac arrest.

Ross Koppel, Sean Smith, Jim Blythe, and Vijay Kothari observed how clinicians skirt security policies in their 2015 research paper, Workarounds to Computer Access in Healthcare Organizations: You Want My Password or a Dead Patient? Here’s a taste of what they found:

Sticky notes with login credentials forming “sticky stalagmites” on medical devices and in medication preparation rooms.

Clinicians offering their logged-in session to the next clinician as a “professional courtesy,” leading to physicians ordering medications for the wrong patient.

Doctors and nurses creating “shadow notes” for patients, outside of the approved IT tools.

A vendor distributing stickers for workers to “write your username and password and post on your computer monitor”.

Nurses circumventing the need to log out of COWs (Computer on Wheels) by placing “sweaters or large signs with their names on them,” hiding them, or simply lowering laptop screens.

This is healthcare security failing in real time.

But before we start waving fingers (or grabbing pitchforks), we need to ask why clinicians engage in such risky workarounds to security. The answer, according to the paper’s authors, is that healthcare security systems are not designed for the realities of workers. They write: “Unfortunately, all too often, with these tools, clinicians cannot do their job — and the medical mission trumps the security mission.”

In a separate paper detailing the friction between end users and healthcare security, Dr. Ross Koppel and Dr. Jesse Walker describe the reality of a clinician’s security experience:

“Asking employees to log in to a system with elaborate codes, badges, biometrics, et cetera 200 or 300 times a day just generates circumventions—not because of laxness or laziness, but because they are just trying to do their jobs and fulfill the mission of the organization.”

This disconnect between IT and security teams, management, and frontline workers isn’t unique to healthcare. Professionals in every industry can learn something from how the situation got this bad, and what can be done to fix it.

Why healthcare data breaches happen

We’ve established that healthcare security is not responsive to the needs of clinicians – but whose fault is that? To gain a better understanding, I reached out to Dr. Ross Koppel.

When I asked him whose responsibility it was to get better systems — he didn’t mince words. “99% is the fault of the system, the IT team, the CISO, etc. Also the board, in that they don’t hire enough cybersec folk,” said Koppel.

Those who read Koppel et al’s study resonated with that sentiment. In a forum discussing the paper, one commenter shared that when they worked for a medical software company, they encountered resistance every time they suggested talking directly to end users.

“It remains one of the few jobs where I had to raise my voice regularly, because every decision involved someone saying ‘well, how can we know how the end users would use this,’ and me gesturing emphatically out the conference room window at the hospital across the street. I wanted to walk over and ask people for help, but they hated that idea…”

And of course, it’s worth mentioning that the healthcare sector is far reaching, and it’s not just hospitals and clinicians that share responsibility over sensitive patient data. The Change Healthcare leak is one harrowing example of healthcare business associates like insurance dealers leaking sensitive health information. Similarly, the HSA provider HealthEquity similarly saw a data breach that leaked the personal information of millions. The hackers first gained access by using the compromised credentials of one of HealthEquity’s partners.

The communication problems of the healthcare system clearly don’t stymie bad actors, who are very adept at using one breached system to gain a foothold into another, increasing the vulnerabilities and attack surface surrounding patient information. But for the system itself to become more secure, we have to start with the data, and the hospitals that collect it.

A disjointed system

For a better understanding of why healthcare cybersecurity is the way it is, a closer look at the decision makers is required. In Proofpoint’s Cybersecurity: The 2023 Board Perspective report, only 36% of board members in healthcare said they regularly interact with their CISO — by far the lowest of all sectors surveyed. Given what we know about healthcare security and its ripe attack surface, that statistic alone should be sending shockwaves through the industry…should be.

The Koppel et al study saw the same lack of communication about security, writing that: “Cybersecurity and permission management problems are hidden from management, and fall in the purview of computer scientists, engineers, and IT personnel.”

This disconnect between board members and CISOs plays out between IT/Security teams and end users as well. The Ponemon Institute study cited earlier found that 47% of IT and security practitioners in healthcare are concerned that employees don’t have a grasp of how sensitive and confidential the information they share via email is.

According to those same IT and security practitioners, the top three challenges they experience in having an effective cybersecurity posture are expertise, staffing, and budget. If we read between the lines, it’s really budget, budget, and budget, since that’s what pays for staffing and expertise. With healthcare board members' (perhaps willful) lack of insight into their organizations' security, they’re communicating loud and clear that security isn’t a priority when it comes to spending money.

The fallout of healthcare data breaches

If you’ve become numb to data breaches, I’d understand. The formula for a data breach article usually consists of a headline that states how many thousands or millions were affected, what data was compromised, and then a statement from the victim on what they’re doing to mitigate the issue for the affected individuals. Then you go on with your day because that’s just how it is in cybersecurity. But in the past few years, healthcare breaches have reached a level of seriousness that should shock even the most jaded observer.

Take for instance St. Margaret’s Health, hospitals serving Spring Valley and Peru, Illinois. A February 2021 ransomware attack caused the closure of the 120 year-old hospitals, leaving its communities without a local medical center. The ransomware attack endured for months, shutting down the hospital’s IT network, email systems, and its EMRs. These disruptions left the hospital unable to collect payments from insurers, therefore also unable to charge any payments as the attacks raged on.

As DarkReading posits: “Often many small, midsized, and rural hospitals lack a full-time security staff. They also have a harder time getting cyber insurance, and when they do, it can cost more for less coverage.”

Patients pay the price

When these ransomware attacks occur, it’s not just the hospitals or healthcare facilities that are affected — it can reach patients. A ransomware group, Hunters International, breached the Seattle-based Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and sent blackmailing emails not only to the hospital, but to over 800,000 patients as well. The threat actors threatened to leak their protected health information — from social security numbers to lab results — but that didn’t work as effectively as they’d hoped. Thus, they needed to escalate the stakes.

Once the extortion emails failed, Hunters International took extreme measures to force payments. They threatened to swat patients at their homes. Swatting, a type of harassment where threat actors call the police repeatedly about a fictitious crime, often results in armed officers arriving at a specified address.

Although there is no report that the swatting threats to Fred Hutch patients materialized, other hospitals have recently been swatted, and it’s not hard to imagine ransomware criminals on the other side of the world eventually crossing this line to get a payout. Patients must wrestle with the possibility of such a traumatic and stressful event happening, as well as all the other ways their sensitive data could be weaponized against them. And that’s not the full extent of these data breaches.

When ransomware attacks affect hospitals, it’s not just sensitive data or a potential shuttering that are on the line, but the care that determines someone’s life. Ardent Health Services, a healthcare provider across six U.S. states, disclosed in November 2023 that its systems were hit by a ransomware attack, leading them to instruct all patients requiring emergency care to go to other hospitals — more often than not, hospitals that were further away – costing valuable time that can be the difference between life and death.

All these stories are a testament to how, when healthcare professionals' medical mission is at odds with security policies, more often than not, patients bear the brunt of it. So while we can empathize with clinicians going around security procedures, we can’t excuse it.

How to build healthcare security systems to clinicians' needs

When I asked Dr. Koppel how these healthcare security systems could be functioning better, he advised starting with end users. “Study how work is actually performed,” he said. “View every workaround as a blessed symptom that enables you to see what is wrong with the current workflow process or rules.”

With all of the blessed symptoms we’ve covered, there has to be a cure.

Budget

Although we already covered the sizable disconnect between board members and CISOs, 85% of healthcare board members expect an increase in their cybersecurity budgets in 2023 and beyond – we can only hope!

An increased budget will allow these IT and security teams to rework broken systems. Those same systems that are the bane of these clinicians' daily routines and partially responsible for poor security can now evolve into more realistic and reliable systems.

For starters, rather than having a bunch of different authentication methods, ditch the passwords and adopt more secure (and less disruptive) methods such as hardware and/or biometric authentication. This lets workers authenticate securely and instantaneously, without the need to remember passwords.

On top of that, make additional IT and security hires, so they’ll have the time and bandwidth to train and users, ensure protocols are actually being followed (not just by hospital workers, but by business partners as well), and adjust them when you (inevitably) need to. Think of it this way: it’s cheaper than shutting down.

User-first security

From what we’ve gathered, healthcare security operates on what should theoretically work, but clinicians don’t work in theory. They need practical security measures.

Healthcare workers are often understaffed, overworked, and under pressure to see as many patients as possible. If you’ve introduced an authentication measure that takes 10 seconds — how do you expect these healthcare workers, who are already under extreme stress, to find the time to authenticate hundreds of times a day?

The good news is that fixing those settings doesn’t have to require big investments; you can tweak the tools you already have in place.

If you communicate with your clinicians, you’ll most likely find that things like session sign outs don’t need to occur every 30 seconds. The less frequent they become (within reason), the less incentive clinicians will have to institute workarounds.

That said, when you do come up with a workable policy, you also need to be firm in enforcing it. For instance, doctors and nurses keeping “shadow notes” opens the possibility that sensitive data is being kept on public hard drives and other unsafe places, potentially in violation of HIPAA.

To address a workaround of this magnitude, once again, discuss with your clinicians why they are doing it, then work together to find a safer, non-shadow-IT alternative where they can log information. After that, IT and Security teams will need to actively seek out unapproved shadow notes applications and files, eradicate them, and put that particular workaround to bed.

Look, no security system is perfect. But if security teams establish effective working relationships with the end users they defend, progress can be made. Listening to end users, educating them about the importance of security, and then firmly and fairly enforcing policies is the heart of Honest Security.

Honest Security is a philosophy that lets end users and IT and security teams find common ground, relying on communication rather than top-down mandates. As we’ve seen from the stories of healthcare workarounds, restrictive, cumbersome security workflows won’t work, even if it’s the “right way.” The facts tell us this!

This can mean letting go of automation in favor of giving users agency. For instance, doctors won’t tolerate an MDM-forced restart of their computer while they’re entering patient notes, but they can do the restart themselves, on their own time, with adequate education and consequences.

Education

One of the tenets of Honest Security is: “End-users are capable of making rational and informed decisions about security risks when educated and honestly motivated.”

Bottom line: clinicians are never going to make time for even the best-designed system, unless they understand why it’s important.

But healthcare is like many other industries, in that education is treated as an afterthought, or a compliance checkbox. Only 57% of IT and security practitioners surveyed say they conduct regular training and awareness programs.

But from our own shadow IT report, we know that security training is surprisingly popular, if it’s done right. 96% of workers (across teams and seniority) reported that training was either helpful, or would be helpful if it were better designed. So give it to them! That takes planning and commitment, since clinicians' time is valuable, and scheduling is a challenge, but you won’t get results without it.

Communication is the best medicine

When accessing data is a matter of life or death, there is no time for finger-pointing. For healthcare security to improve, it’s paramount to get to the crux of the issue — instituting security policies that reflect the needs of clinicians without sacrificing the security of patients or the organization.

And while healthcare is a particularly high-stakes industry, the lessons here apply everywhere. Any CISO or security professional could benefit from opening their eyes to the security workarounds in their organization, and using them as opportunities to learn from their end users about how the system could work better for everyone.

Want to read more security stories like this one? Subscribe to the Kolidescope newsletter!

by Kenny Najarro on

by Kenny Najarro on