In 2022, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the most powerful data privacy law in a generation, was used to fine a nosy neighbor.

An unnamed Spanish citizen had two home security cameras pointed toward a public road. This got attention from their city council, who filed a claim with the Spanish data protection authority (AEPD).

Home security is one thing, but GDPR has some pretty strict requirements on how citizens’ data can be processed. For one thing, you have to collect only the minimum data necessary for your purpose; recording everyone who passes by your house is going a little overboard. And while the homeowner had hung up a notice about the cameras, it lacked important information, like who owned the recordings.

For this, and other issues, the AEPD found the individual in violation of GDPR. They were ordered to move their cameras, hang up notices about the recorded data, and pay a fine of 1,500 euros.

Since GDPR enforcement began, plenty of companies have had an unspoken belief: “I’m too small for the EU to notice.” But data authorities are paying attention to even the smallest cases. And in recent years, GDPR enforcement has only been ramping up in scale and intensity. These days, if you do business in the EU, you have to do more for GDPR compliance than cross your fingers and play the odds.

Note to readers: We’re going to be starting with an overview of the GDPR basics. For readers who need a refresher, read on. For readers who are already familiar and want to get straight to the juicy stuff, we’ll forgive you if you skip ahead to the section titled: Recent changes to GDPR enforcement.

What is GDPR?

GDPR is a regulation that formalizes and enforces the data privacy rights of European Union citizens. It was first published in 2016, and enforcement began on May 25th, 2018.

Remember 2018? GDPR had built some impressive hype, in no small part because it came with hefty consequences for infringement – violating companies could be charged up to 4% of their global turnover for a fiscal year.

Invasive ad companies were pulling out of Europe with their tails tucked between their legs, academics were celebrating “the most consequential regulatory development in information policy in a generation,” and the scrappy little multinational data regulation even managed to beat Beyoncé in Google search volume (for like, a couple of days, but still).

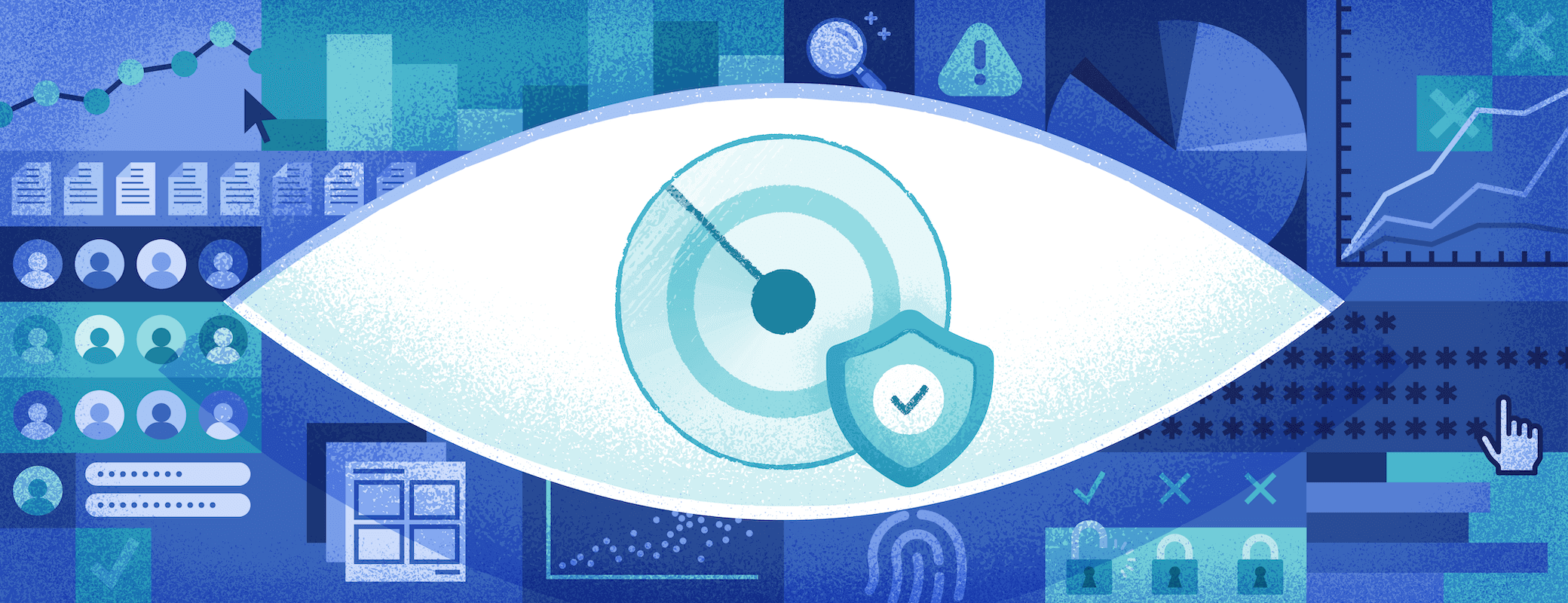

All that build-up aside, it feels like it still took a few years to see GDPR truly kick off enforcement. Legal proceedings are never zippy, for one thing, and only a fraction of GDPR fines receive media attention.

But recently, GDPR has been getting some renewed buzz. Some very visible rulings against big tech companies saw GDPR fines topping 2.06 billion euros in 2023.

And while those big fines make a lot of noise, GDPR has been picking up steam at every level. Since enforcement began, the GDPR enforcement tracker from CMS has shown a general upward trend in fines at various amounts being levied against companies of various sizes. From 2019 to 2023, we went from only 143 public cases a year to closer to 500.

And remember – most fines aren’t notorious or big enough to go public. CMS looked through aggregate numbers of the non-publicized fines, and notes that the less notable cases make up the vast bulk of GDPR enforcement.

This “ramp-up of enforcement,” as CMS calls it, has gotten GDPR some renewed interest in the past few months alone.

Given all this attention, you probably have a decent idea of what the law is and how it impacts businesses. But let’s start off with a refresher on the basics.

What data is protected by GDPR

The EU takes a broad definition of “personal data.” There are the obvious things, of course, like names and mailing addresses. But any information that could conceivably be used to identify someone is considered enforceable. That includes information like IP addresses, working hours, race, religion, and even subjective data like people’s opinions.

The basic rule is that if information could be connected to a specific individual – either on its own or by connecting it with other data – then it’s protected.

When is it okay to collect PII under GDPR?

Protected information can be collected and processed if the subject gives their informed consent.

However, data can be collected without consent in specific cases where the benefits outweigh any privacy compromises. By and large, these cases are pretty sensible. Banks can process data to prevent fraud, for instance, and hospitals can process your data to treat urgent injuries.

The thorniest provision for this, however, might be that companies are allowed to collect data to serve “legitimate interest.” As we’ll see later, some companies have adopted an overly broad interpretation of that term. Keep in mind – when it comes to marketing, users’ privacy will almost always outweigh companies’ interests.

Who GDPR applies to

If GDPR applies to your company, you hopefully already know that. But just to be clear, GDPR applies to any controllers that:

- Are based in the EU.

- Aren’t based in the EU, but sell goods or services there, or collect and process the data of European citizens.

It’s also worth noting that, Brexit aside, the UK adopted their own (basically verbatim) copy of the GDPR, so you can go ahead and lump them in with everything else we say in this article.

We’ll go into more specifics later on the responsibilities of controllers – especially for the overseas controllers out there. But spoiler alert: one of a controller’s primary obligations is to protect data from unauthorized access, so we will be talking about security.

Rights of subjects

GDPR articulates certain fundamental rights that subjects have when it comes to their data. These rights include things like providing subjects’ data to them when it’s requested, as well as erasing or correcting that data when necessary.

GDPR also places the impetus on companies to make these rights easy for users to exercise. Your company’s ability to comply will often come down to your policies around data transparency, governance, and security. You can’t fully erase someone’s data, for instance, if you aren’t sure what devices have already downloaded it or what apps your employees are using to process it.

Recent changes to GDPR enforcement

Again, remember 2018? It’s safe to say that the GDPR fervor has died down a smidge since then (Beyoncé’s still going strong, though).

After a few years of enforcement, we grew jaded. There were some fines levied, sure, and the creepy neighbors of the world were hopefully being more cautious with their doorbell cameras.

But GDPR hadn’t cracked any of the broader systemic issues with data privacy. Its impact on online tracking rates was marginal at best, the world’s data brokers weren’t exactly taking a hit to profits, and business pros were still using the cold calculus of “why pay for security when you can just pay the fine for a breach?”

As Austrian privacy campaigner Max Schrems stated in 2022: “After a first moment of shock, a large part of the data industry has learned to live with GDPR without actually changing practices."

However, as Wired reported that same year: “Europe’s data regulators claim GDPR enforcement is still maturing and … improving over time.”

It sounded like lip service, but very recently we’ve seen some major changes to how GDPR is enforced–especially in cross-border cases.

GDPR’s cross-border problem

In all honesty, enforcement was probably always doomed to have an uneven start. The EU is composed of disparate countries with disparate systems of government, after all.

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) was established to make sure that GDPR was being enforced consistently. But each EU Member State was still in charge of forming its own independent “supervisory authority,” to investigate and enforce GDPR rulings in their country.

What about cross-border cases, where companies process data from citizens in more than one EU state?

It’s simple!

The country that hosts the company’s main establishment (“the place of its central administration in the union”) would become the “lead supervisory authority.” They’d be responsible for overseeing the cases levied against that company. It’s a one-stop-shop mechanism to keep cross-border collaboration streamlined and efficient.

… Right?

Ireland vs The EU

The thing is, tech companies don’t tend to build their headquarters in nations known for being tough on corporate malfeasance.

Ireland and Luxembourg were two countries known for courting big tech with low corporate tax rates and other business-friendly regulations. Suddenly, they became the supervisory authorities of the very corporations they’d pinned their economic hopes on.

Luxembourg, for instance, became the primary regulator of Amazon, a company with about twice as many employees as Luxembourg has citizens. That didn’t stop the Luxembourg authority from levying a hefty fine against Amazon, but there was plenty of debate around the wisdom in provoking their country’s second-largest employer.

Meanwhile, The Emerald Isle had been particularly aggressive in rolling out the red carpet to Big Tech. The Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) became the lead regulator in cases relating to major companies like Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Meta.

Well before GDPR, in cases like the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the DPC had already proven themselves willing to overlook Silicon Valley’s privacy sins. And their approach to GDPR enforcement didn’t invite much new confidence. Nowhere is this more clear than their attempts to enforce GDPR policies on Meta.

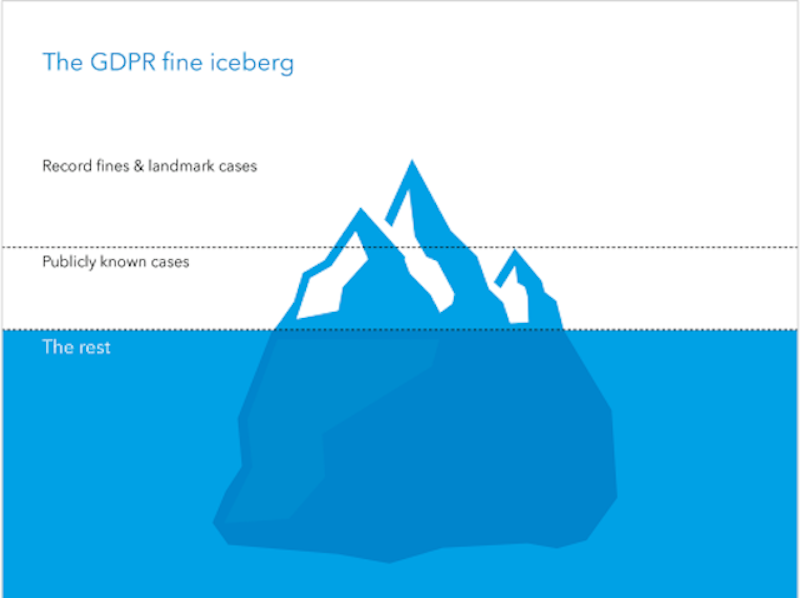

Meta had been under fire by privacy activists since literally day one of GDPR enforcement. Of particular concern was Meta’s transfers of EU citizens’ data overseas for processing. In fact, investigation into their practices in 2020 led the European Union to invalidate Privacy Shield, the whole legal mechanism for smoothly moving data across the Atlantic.

It would be three years before a new, slightly tougher mechanism was in place, but for that whole time, Meta continued their data transfers as usual, citing their need to fulfill contractual obligations to customers.

Suffice to say, despite hastily updating their terms of service with a clause indicating consent to data monitoring, Meta wasn’t impressing anyone with their GDPR compliance efforts.

And the DPC wasn’t impressing their fellow Member States. Despite the severity of Meta’s infringements, after five years of investigation, they sent out a drafted decision to fine the company a maximum of 59 million pounds.

Other nations made some strong objections. The DPC, in their words, “determined that it would not follow [the objections] and/or that they were not relevant and reasoned.” The case was referred to the EDPB for a final decision in 2023.

- Meta would be fined 1.3 billion (note the b) dollars.

- They weren’t buying Meta’s “contractual obligation” argument.

- Meta had to suspend data transfers.

- Meta had to stop processing or storing in the U.S. any of their illegally gained data.

- Meta was banned from processing personal data for behavioral advertising across the European Economic Area (EEA).

This wasn’t the first time that the DPC had issued rulings that were out of step with the prevailing legal consensus. As Derek Scally reported for The Irish Times, “in seven EDPB interventions in national decisions to date, all but one have involved the Irish regulator.” He went on to say that critics linked the consistent pattern of intervention “…to how the Irish regulator – faced with a choice – will always choose the most tortuous, lengthy and expensive legal route to a decision rather than a simple application of EU law.”

The Meta case, however, invited particular frustration. For the EDPD to overrule a regulator’s decision requires a two-thirds majority vote. And Scally reported that in the Meta ruling, not a single one of the 30 member states in the EDPB sided with Ireland.

The EU vs you

The thing is, Meta’s pretty big.

When hearing about such egregious violations, it would be natural to think: “Europe’s not going to care about my lil old non-compliant company.”

But remember the home security enthusiast from earlier – most cases aren’t big enough to get national attention.

That’s not to say that the big cases don’t have an impact on the little ones. The recent big tech enforcement actions bring attention and notoriety, which leads to a general tightening of the policies used to enforce all cases. For instance, Meta’s ruling seems to have marked a tipping point in the EU’s patience not just with Ireland, but with overseas companies in general.

On February 14th, 2024, the EDPB published a strongly worded Valentine (or guidance) around the one-stop-shop, enforcement-where-you’re-established mechanism.

The one-stop-shop will now only apply for controllers that can prove that their European main establishment:

- Is the main establishment in charge of making decisions about how and why data gets processed.

- Has the power to implement those decisions.

If companies have no European main establishments that fit the bill, one-stop-shop doesn’t apply, and they’ll be at the mercy of any and every country that’s receiving complaints about them.

This is a clear attempt to nerf overseas companies that set up puppet establishments in corporate-friendly EU countries. EDPB even takes the time to specify that “the Board also recalls that the GDPR does not permit ‘forum shopping’ in the identification of the main establishment.”

Listen. There’s no delicate way to put this, so I’ll be using their full name in order to convey a proper amount of severity.

The European Data Protection Board is pissed. Legal bodies don’t put scare quotes around “forum shopping” unless they’ve been driven to the edge of a blind rage.

This new guidance comes on the heels of The European Commission in 2023 committing to oversee every large-scale GDPR case. Later that year, they committed to strengthening and streamlining cross-border GDPR investigations so rulings would move faster.

These strengthened restrictions are going to impact cases at every level of the GDPR. Meta was just the Great White Shark that showed them their boat was too small.

To summarize: in the years since GDPR’s passage, the European Commission has stepped up its commitment to making enforcement better, faster, and stronger. And when it comes to companies that take a laissez-faires approach to people’s rights, there’s no target too big or too small.

GDPR’s controller responsibilities, and how they’re being enforced

So, what are the duties of a controller with a renewed dedication to compliance? GDPR explicitly lays out several responsibilities for data controllers. We’re going to focus on the more commonly infringed responsibilities, along with brief examples of what happens when companies fail to meet them.

Transparency

Controllers need to tell people what’s processed, and make it easy to consent or not consent to sharing their data.

H&M

In 2020, H&M received what was then a record-setting fine of 35.3 million euros. They were cited by the Data Protection Authority of Hamburg (HmbBfDI), which might mark this article’s tipping point for acronyms.

H&M was fined for keeping excessive records on employees, including their religion and health data.

GDPR has made one thing about employee data clear: “It is basically impossible for employees to give voluntary consent to their employer … because of the unequal negotiation power…”

The H&M case, however, belongs in this section because some of the employee data had been gathered during informal chats with managers – meaning there was absolutely no transparency around its use in processing.

Data protection by design and default

This responsibility states that controllers are obligated to default to doing everything they can to protect the data they gather, as well as only collecting the minimum amount of data necessary for their stated purposes.

Amazon France

In January of 2024, Amazon France Logistique got fined for a few things (including shoddy passwords). Of particular interest was the court’s ruling on productivity scanners. Amazon was scanning and logging employee “idle time” down to the millisecond.

The court’s conclusion was that yes, companies can assess productivity. But there are plenty of ways to measure that without collecting such a downright obsessive amount of data. As such, Amazon was in breach of data minimization principles.

Notification of data breaches

If a controller suffers a breach of people’s personal data, they have to report it to the supervisory authority within 72 hours. And when it’s likely to result in any risk to the data subjects, they have to report the breach to them as well.

In 2020, Twitter (now X) was actually the first big tech company to be fined by the DPC: $546,000 for failing to report a breach in time.

The DPC, in what would soon become a pattern, first tried to fine Twitter by a much smaller amount, saying that the failure to report was a result of “negligence” rather than avoidance. The EDPB, in what would soon become a pattern, stepped in and increased the fine.

Security of data processing

Controllers are obligated to follow strong security principles and do all they can to protect data.

British Airways

In 2020, British Airways received what was also, at the time, a record-setting fine. They had experienced a highly preventable data breach, and the courts lacked sympathy for a company that had failed to implement adequate security, such as MFA.

Data protection impact assessment

If a controller adopts new technology or practices that are likely to affect people’s data, they have to do a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA). This requires them to document their anticipated privacy risks, and to specifically outline the systems they’ll implement to follow GDPR principles.

ICS

Plenty of companies have failed to comply with this guideline at all. But Dutch credit card company ICS was fined 150,000 euros for, basically, doing a lazy job with their DPIA. It’s another sign that GDPR can be unforgiving to controllers that don’t seem to take compliance seriously.

Records of processing activities

Controllers are obligated to keep records of what, how, why, where, and how long data is processed. This is an important responsibility to note. Fulfilling just about any of the data subjects’ rights listed above requires having an organized record of individuals’ data.

Clearview AI

Clearview AI is a small American facial recognition company that used random photos of citizens worldwide to train their data. They were found in violation of numerous parts of GDPR. And calculating the total cost of their fines is a little tricky, since multiple EU countries have issued fines in the millions by now.

But of interest is Clearview AI’s citation for failing to comply with subjects’ “right to erasure.” The company had no actual way of searching for the pictures taken of specific people, unless the victim were to also provide more pictures of themself to the company as a search filter. Which, as it turns out, does not fulfill their record obligations.

To get GDPR compliant, start with security

In 2022, John Edwards, the UK Information Commissioner, issued a fine of 4,400,000 pounds to a construction company that failed to keep its staff’s personal data secure.

He stated: “The biggest cyber risk businesses face is not from hackers outside of their company, but from complacency within their company. If your business doesn’t regularly monitor for suspicious activity in its systems and fails to act on warnings, or doesn’t update software and fails to provide training to staff, you can expect a similar fine from my office."

(Hey IT and security teams, try sharing that quote with your executive leadership.)

Of the fine violation types, “bad security” ranks third both in terms of the total cost of fines and the total number of them. But really, every aspect of the GDPR is about data protection, and that means that cybersecurity is a core element in getting compliant.

Now we’ll go into more detail about how you can use security to improve your GDPR compliance. Fair warning, we’ll be using our own product, 1Password Extended Access Management (XAM), as an example. But let’s be clear: no single piece of software can make your company compliant with GDPR. Bringing your data collection and security policies in line with GDPR is a cultural and philosophical project, just as much as a technical one.

Data minimization

If there’s any company that could truthfully claim that collecting data was a business necessity, it would be Meta. And the EU still didn’t give them a pass; it’s hard to think that they’ll be any more forgiving of companies that are collecting more data than they need for a rainy day.

So, it behooves teams to start looking at processing policies with the goal of data minimization.

For data minimization, the first step is to look at your systems and data flows. The DPIA assessments we mentioned earlier aren’t just required; they’re a useful tool to get your team to ask itself some questions.

For instance: What do you collect, why, and for how long? What data is actually essential for your business? And remember, these are questions you should be asking about the data you collect on employees, not just customers.

XAM follows these principles in the monitoring of employee devices. We never monitor things like browser history or take screenshots of worker activity; there’s no security benefit to knowing what songs your employees listen to on Spotify.

When it comes to employee device oversight, XAM makes it easy for your team to document the reasoning for processing the data you do.

Access management

On a basic security level, secure and encrypted passwords are hugely important, and way too many GDPR fines cite companies for poor password policies.

XAM manages access through 1Password’s Enterprise Password Manager. This enables employees to use strong unique passwords for every account, because they only have to remember one account password.

But XAM goes beyond that, because it also manages access at the device level. That means that only verified devices – like a user’s work computer – can access sensitive data.

This significantly reduces the attack surface for bad actors. It also helps teams provably contain data flows across a controlled number of users and devices.

Data management

Do you know where all your data is?

If your employees are using unapproved apps and personal devices, then the answer is probably no. It’s easy for sensitive data to leak out via shadow IT, and end up in the hands of bad actors.

XAM manages these issues via device trust, which boils down to device posture checks that scan for unauthorized apps, as well as on-device authentication that ensures that only recognized and healthy devices are accessing sensitive data (making sure that data stays where you can see it).

And since software vulnerabilities are a growing cause of breaches, XAM also ensures that your endpoint devices are updated and patched, and gives your team verifiable logs of your update process.

Transparency

“Transparency” could be the one-word motto of GDPR. But you can’t be transparent until you take the time to think about what you monitor and why.

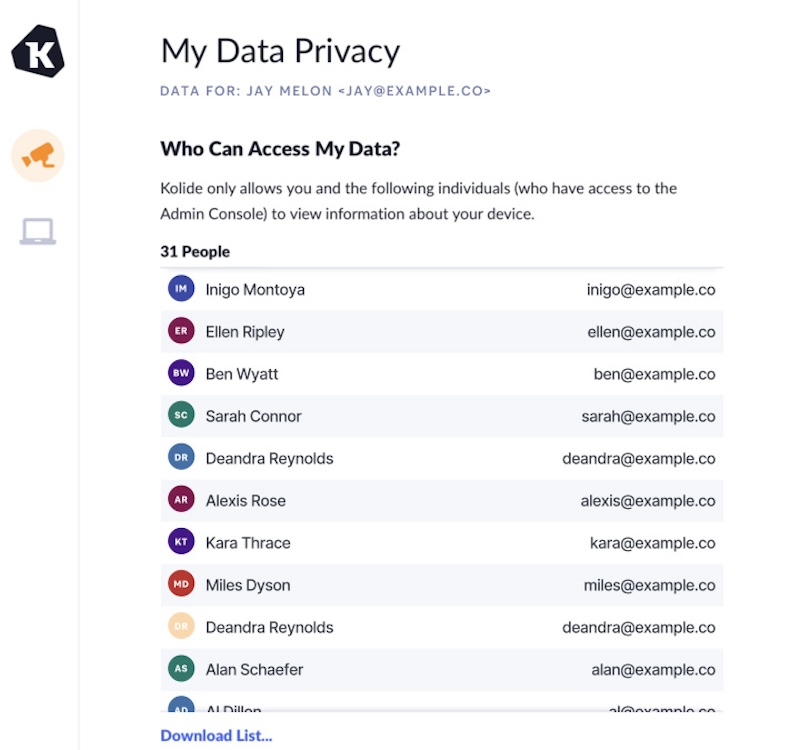

The notion of transparency is deeply ingrained into XAM, which features a privacy dashboard that shows end users:

- What data is being accessed.

- Who is accessing it.

- What the purpose of accessing that data is.

Overall, people deserve to know when and why their data is accessed. And XAM provides a useful model for how to be transparent with your teams.

GDPR compliance requires a cultural shift

Achieving GDPR compliance isn’t going to be simple. We live in a world where companies and users alike are resigned to the idea that our data belongs to no one and everyone, and that’s a tough mindset to break out of. To follow GDPR, it’s not enough to be better than Meta. Your teams need to be better than what has become the default.

The GDPR is a law built on the revolutionary idea that “people have rights when it comes to their personal data.” It’s a refreshing principle, and one that most people want to honor.

Compliance is a worthy goal, but the worthier one to strive for is “respecting the data of the people you serve.” Meeting that goal is going to take effort, and may even require a shift in your company’s fundamental culture around privacy. But the rewards will be worth the work.

So go ask your company’s leadership if you plan on minimizing risk with GDPR next year. If the answer is yes (and it really should be), then you can use this article to present some practical next steps.

by Rachel Sudbeck on

by Rachel Sudbeck on